Any increase in Ireland's corporation tax rate as part of a financial bailout could hurt the country's rapidly expanding pharmaceutical industry, currently its largest contributor to corporation tax.

Ireland is in talks with the European Union and the International Monetary Fund regarding a potential rescue package to stabilise the Irish banking system and protect the euro. So far Irish leaders have ruled out any increase in its corporation tax rate as part of the deal. But media reports have suggested that member states may try to force an increase to guarantee a return on their investment.. read more.

Field of Science

-

-

Change of address7 months ago in Variety of Life

-

Change of address7 months ago in Catalogue of Organisms

-

-

Earth Day: Pogo and our responsibility10 months ago in Doc Madhattan

-

What I Read 202411 months ago in Angry by Choice

-

I've moved to Substack. Come join me there.1 year ago in Genomics, Medicine, and Pseudoscience

-

-

-

-

Histological Evidence of Trauma in Dicynodont Tusks7 years ago in Chinleana

-

Why doesn't all the GTA get taken up?7 years ago in RRResearch

-

-

Harnessing innate immunity to cure HIV9 years ago in Rule of 6ix

-

What kind of woman would pray for health or use spiritual healing?9 years ago in Epiphenom

-

-

-

-

-

-

post doc job opportunity on ribosome biochemistry!11 years ago in Protein Evolution and Other Musings

-

-

Blogging Microbes- Communicating Microbiology to Netizens11 years ago in Memoirs of a Defective Brain

-

Re-Blog: June Was 6th Warmest Globally11 years ago in The View from a Microbiologist

-

-

-

The Lure of the Obscure? Guest Post by Frank Stahl13 years ago in Sex, Genes & Evolution

-

-

Lab Rat Moving House14 years ago in Life of a Lab Rat

-

Goodbye FoS, thanks for all the laughs14 years ago in Disease Prone

-

-

Slideshow of NASA's Stardust-NExT Mission Comet Tempel 1 Flyby15 years ago in The Large Picture Blog

-

in The Biology Files

Have you really reduced the world's carbon footprint?

I do not usually criticise TED talks but this time I am making an exception. In this talk John Hardy the founder of Green School spoke about how he founded and developed Green School. He said that he was living a happy life till he saw Al Gore's movie, An Inconvenient Truth. It woke him up and made him realise that the Earth is fragile and that we must learn to take better care of it and reduce our carbon footprint.

In an attempt to educate he built the Green School, a place built completely out of bamboo. Kids are not only taught the usual subjects but also taught how to live 'whole lives'. The students learn to the traditional things of the Bali locality, plant rice, cut bamboo and build structures. They have made the whole place so green that there is almost no man-made synthetic material in the building. They have even designed toilets such that you don't have to flush. To know more you can watch the video at the end of this post. It's all a very fascinating idea and quite well done.

At one point he mentions that his school has a 160 students from 25 countries and because he wants the locals to be involved. There are scholarships for Bali students and also 2o% seats reserved for them. It all sounded a bit odd to me. So out of curiosity I visited their website and realised that of course Bali students need scholarships to attend this school considering how expensive it is.

Non-refundable fees for all students $2750, then annual fees for Nusery and Pre-K $5000, for Kindergarten $8000, for Grades 1-5 $9000, for Grades 6-9 $10000. It makes me think that these students who come from 25 countries, must have really rich parents to be able to support such an education. Which also means that they are probably not residents of Bali but really settled in those 25 different countries.

Now if they come visit their kid once a year for the annual gathering and the kid travels back to his home country every summer then per kid there are 6 plane travels per year (2 parents and 1 kid). Assuming 80% students (128) are from abroad it would mean 768 plane travels per year for the whole school. Assuming a mean distance of 9000 miles for each ride, it would mean a carbon footprint of 1,228,800 kg of carbon dioxide. Assuming a mean distance of 4500 miles would still mean a carbon footprint of 614,400 kg of carbon dioxide

Now how much did they reduce the world's carbon footprint by using bamboo to make that school again?

Porous silica makes funky coloured films and could lead to warmer windows

Using nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) from wood pulp, Canadian researchers have for the first time prepared mesoporous chiral nematic structured silica materials that may have potential as tuneable reflective filters in smart windows, chiral catalysts in synthesis and even as optical sensing devices.. read more.

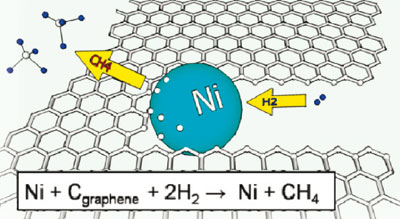

Chemistry that can change the world – II

|

| Ni nanoparticles absorb carbon from graphene edges which then reacts with H2 to create methane |

How 'green' is your detergent?

Fragranced household products, even those labelled as 'green', can emit large numbers of hazardous chemicals that aren't listed on their labels, US researchers have confirmed. The research raises questions about the risks associated with these products and regulating the claims on their labels.

A team led by Anne Steinemann at the University of Washington in Seattle, US, used gas chromatography to analyse the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) released from 25 of the top-selling US products such as detergents, hand sanitisers and air fresheners, and found that they emit many hazardous compounds... read more.

A team led by Anne Steinemann at the University of Washington in Seattle, US, used gas chromatography to analyse the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) released from 25 of the top-selling US products such as detergents, hand sanitisers and air fresheners, and found that they emit many hazardous compounds... read more.

I know why the Daily Mail's news sticks in our heads

If you are a reader of newspapers in the UK and are interested in reading science news then you will also know the Daily Mail (or the Daily Hate, as some people like to call it). The reason why it is famous is not because it does really great science news, but because it does exactly the opposite. To give you a taste of what some people think of it, here is a review:

Researchers from Princeton University found that 'ideas published in hard-to-read fonts are difficult to learn but easier to remember'. Futurity reports:

PS: I am not the first person to think that they use difficult fonts, see this.

The Daily Mail is an awful, awful paper. Will happily skew the facts to make Britain out to be a country swimming with knife-wielding immigrants, benefit cheats and general disorder, turning readers into frightened reactionaries. Regularly get pulled up by media watchdogs because of journalism that is anecdotal, twisted or just plain made up. I find it dictatorial in its opinions at others, I believe there's no newspaper which has a more dangerous effect on British society.But my point is not to defame the Daily Mail, there are many who do it and it still enjoys a really large readership. I want to tell you about a piece of research that I read about which might explain why the Daily Mail's headlines (or even the content) stick in your head. The short answer is hard-to-read fonts.

Researchers from Princeton University found that 'ideas published in hard-to-read fonts are difficult to learn but easier to remember'. Futurity reports:

Apart from all the fear mongering tactics that the Daily Mail uses, these fonts might be one big reason why people tend to remember what the Mail said more that what the Times said!In the first, 28 participants between the ages of 18 and 40 were brought to a lab at Princeton and asked to learn about extraterrestrials, to limit the amount of already known information that could influence the test.The material was presented in either easy or challenging fonts. The subjects were given 90 seconds to memorize information about the aliens, distracted for 15 minutes and then tested.Those who read about the aliens in an easy-to-read font (16-point Arial pure black) answered correctly 72.8 percent of the time, compared to 86.5 percent of those who reviewed the material in hard-to-read fonts (12-point Comic Sans MS or Bondoni MT in a lighter shade).

PS: I am not the first person to think that they use difficult fonts, see this.

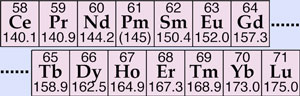

Smuggling key factor in China's rare earth actions

Widespread smuggling of rare earth materials and rapidly increasing domestic demands are key factors in China's recent moves to drastically reduce exports of the sought after elements.In July, China, currently in control of almost the entire global rare earths market, announced a reduction of up to 72 per cent in its exports for the second half of 2010 compared to the same period last year. Despite its position as the world's major producer of rare earth elements, as the materials bleed out from the country, China has attempted to acquire other mines around the globe to maintain its control of the growing global market... read more.

UK carbon capture competition for £1 billion becomes a one horse race

On the same day UK ministers revealed a £1 billion fund for the development of carbon capture and storage (CCS), power company E.ON UK announced it is pulling out of the government's national CCS competition, leaving just one company in the race. In 2007 the government announced a competition to build one of the world's first commercial scale CCS demonstration plants in a bid to strengthen the UK's position as a world leader in cleaner fossil fuel technology. Before E.ON's departure from the race, energy firms BP and Peel Power had already pulled out of the competition in 2008 and 2009 respectively... read more.

Kroto suggests an alternative to peer review

My fellow blogger, wavefunction, in his latest post raised an important issue in science: peer-review. He quotes Sir Kroto in his interview in Nature where he suggests that a new system should be put in place instead of 'the most ludicrous ever devised' that will allow money to be awarded by local institutions not the government bodies. The money should be given in three categories:

- Young deserved researchers

- Researcher whose most recent report was excellent

- Researcher who could not be funded in (2) should be allowed to raise matching funding from industries.

Although Kroto must have given a lot of thought to this before suggesting it, I can see many problems with this system:

Who decides who is a 'deserved' young researcher or who had an 'excellent' report and who did not? That would be your peers too, right? Just that they would be peers from the same local institution instead of peers from world over in your own subject area who would have been in a better position to judge your research in the first place.

How will the government decide how much money to be given to each local institution? If every institution is given equal money would that not be unfair on 'better performing' institutions?

Getting rid of proposals? I thought writing proposals was a very important time in a researcher's career not just because the proposal will give him money to continue his research but also it is that time when the researcher thinks the hardest about his work. He thinks about it not only from the perspective advancing knowledge about the subject area but also how his research plays a role in a wider picture of science and society.

The current peer-review system has problems and we acknowledge that. With all due respect to Kroto, this new system needs to be put forth in a more formal manner and needs to address the issues above for the wider scientific community to take seriously.

Who decides who is a 'deserved' young researcher or who had an 'excellent' report and who did not? That would be your peers too, right? Just that they would be peers from the same local institution instead of peers from world over in your own subject area who would have been in a better position to judge your research in the first place.

How will the government decide how much money to be given to each local institution? If every institution is given equal money would that not be unfair on 'better performing' institutions?

Getting rid of proposals? I thought writing proposals was a very important time in a researcher's career not just because the proposal will give him money to continue his research but also it is that time when the researcher thinks the hardest about his work. He thinks about it not only from the perspective advancing knowledge about the subject area but also how his research plays a role in a wider picture of science and society.

The current peer-review system has problems and we acknowledge that. With all due respect to Kroto, this new system needs to be put forth in a more formal manner and needs to address the issues above for the wider scientific community to take seriously.

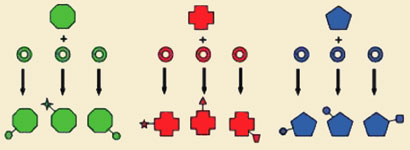

Mining soil DNA for molecular decorators

|

| Enzymes (rings) found in eDNA libraries can modify glycopeptides cores (top) in new ways |

Banik, J., Craig, J., Calle, P., & Brady, S. (2010). Tailoring Enzyme-Rich Environmental DNA Clones: A Source of Enzymes for Generating Libraries of Unnatural Natural Products Journal of the American Chemical Society DOI: 10.1021/ja105825a

Britain should take lessons from USA

|

| Skilled workers may be queuing up to enter the UK, but only a fraction will be allowed in |

In June the government announced a temporary cap on the number of skilled workers from non-EU states that can enter Britain. The move prompted concern in the scientific community that it would lose access to a rich pool of international talent and potentially jeopardise the UK's ability to remain at the forefront of global research.

Before this annual limit is made permanent in April next year, the government could learn lessons from other scientifically advanced nations - also aware of the need to control migration - who have made exceptions for researchers in their immigration policies... read more.

Chemistry that can change the world

After the Economist questioned the value of chemistry last week, today I read with keen interest seeking chemistry in the special article in New Scientist titled ‘50 ideas to change science forever’. Although they have only released 25 ideas in the current issue, I could find at least 10 ideas which were either all chemistry or had a heavy connection to chemistry.

Here's my list....read more.

Here's my list....read more.

Can academic pursuits and money not go hand-in-hand?

This month’s C & EN editorial by Allen J. Bard argues that ‘the culture of academic research has shifted over the past 50 years from research evaluation based on teaching, creativity and productivity to one based simply on the amount of money raised.’

Allen goes on to note that ‘I’ve been to party to tenure discussions that have centred on “scoring two major grants” rather than on the quality of work.’ What is more worrying is that, ‘the fact is that the final decision to fund really comes from the project officers who have often become remote from the frontiers of research and often fall prey to the fad of the mouth’.

He also points out that this has led the universities to focus on demonstrating the ‘economical value’ of the research and their ‘critical mission’ becomes getting more intellectual property (IP) or start-up companies. He concludes by saying, ‘If working closely with students and doing long-term fundamental research is not the goal and money is the important thing, there are more lucrative professions than academic ones for them to pursue.’

If it is true that academics spend 70% of their time writing research proposals then I do agree that Allen has raised some very valid points. But I can’t seem to agree with him that academics should be a pursuit devoid of money.

I think if it’s possible to be an academic who is good at commercialising ideas then one should be. All those monetary benefits of IP that come along with it are a good thing for a university, especially in the economic climate that we are in, where we face major cuts to research spending and increased tuition fees.

Also blaming this capitalistic view of a university for not being able to attract the right talent isn’t right. Academics tend to believe that all the people who do research do it because of the love of the subject and nothing else. Well, they might, but more often than not they may have other reasons. In that respect, the fact that an academic pursuit can lead to a good commercial idea, may actually lure more people than just the subject nerds.

And yet, I cannot agree more that it shouldn’t become the ‘critical mission’ of a university. It may have happened that universities started small, trying to align with the capitalistic nature of the market, by asking academics to ‘think about’ commercialising ideas and over the years reached the point, that they have now, where it has become their ‘main aim’.

How did our nitrogen cycle evolve?

In trying to feed our growing population, we now add twice as much nitrogen to the soil (after chemically ‘fixing’ it to make fertilisers) as microbes fix from the atmosphere. Human activity has skewed the balance in the earth’s nitrogen cycle. But how did the modern nitrogen cycle evolve? A recent review published in Science tries to answer that question and make suggestions about the future. ...read more.

Canfield, D., Glazer, A., & Falkowski, P. (2010). The Evolution and Future of Earth's Nitrogen Cycle Science, 330 (6001), 192-196 DOI: 10.1126/science.1186120

Canfield, D., Glazer, A., & Falkowski, P. (2010). The Evolution and Future of Earth's Nitrogen Cycle Science, 330 (6001), 192-196 DOI: 10.1126/science.1186120

India calls for ambitious increase in science funding

The Scientific Advisory Council to the Prime Minister of India has advised the government to increase its science funding from less than 1 per cent of GDP to up to 2.5 per cent by 2020. It has also recommended overhauling the management of science in the country to increase innovation in the research community.

India is becoming an economic power but without scientific leadership this growth might be unsustainable, says distinguished materials chemist CNR Rao, chairman of the Science Advisory Council. 'This report has been outlined to bring change to the scientific management system and make India a leader in science', he adds... read more.

India is becoming an economic power but without scientific leadership this growth might be unsustainable, says distinguished materials chemist CNR Rao, chairman of the Science Advisory Council. 'This report has been outlined to bring change to the scientific management system and make India a leader in science', he adds... read more.

Sleep more to lose weight? Read this before

Before this piece of research gets out of hand due to shoddy science journalism, it does not conclude that people should sleep longer to lose weight. The paper is titled "Insufficient sleep undermines dietary efforts to reduce adiposity", which means that if you are person dieting to lose fat then sleeping less will undermine your efforts.

The study compares a group of 10 who were dieting, 6 persons slept for 8.5 hours every night for two weeks and similarly, 4 persons slept for 5.5 hours every night for two weeks. And this was repeated on the same subjects after three months. It was seen that the persons who slept less lost less body-fat more fat-free body mass (such as proteins). In the subjects who lost more fat-free body mass they observed increased hunger, which under normal circumstances, will undermine the efforts of a person dieting.

The conclusion is very clear

Nedeltcheva AV, Kilkus JM, Imperial J, Schoeller DA, & Penev PD (2010). Insufficient sleep undermines dietary efforts to reduce adiposity. Annals of internal medicine, 153 (7), 435-41 PMID: 20921542

The study compares a group of 10 who were dieting, 6 persons slept for 8.5 hours every night for two weeks and similarly, 4 persons slept for 5.5 hours every night for two weeks. And this was repeated on the same subjects after three months. It was seen that the persons who slept less lost less body-fat more fat-free body mass (such as proteins). In the subjects who lost more fat-free body mass they observed increased hunger, which under normal circumstances, will undermine the efforts of a person dieting.

The conclusion is very clear

Patients attempting to lose weight should consider getting adequate amounts of sleep in addition to limiting calorie intake to ensure that they retain lean muscle mass and lose fat.The conclusion is NOT what The Seattle Times or Los Angeles Times says:

Moral of the study? Put aside the work, or that late-night TV show, and get some shut-eye. Compared to exercise and diet, it's the easiest part of healthy weight loss.Also remember the limitations of the study

All were nonsmokers aged 35 to 49 years, and none were morbidly obese. Patients were followed for only 2 periods of 2 weeks each, much less than the average amount of time people would usually spend on a calorie-restriction program

Nedeltcheva AV, Kilkus JM, Imperial J, Schoeller DA, & Penev PD (2010). Insufficient sleep undermines dietary efforts to reduce adiposity. Annals of internal medicine, 153 (7), 435-41 PMID: 20921542

Have we solved all the questions in chemistry?

If the polymath Charles Babbage was alive, I don’t think he would have said this: ‘With completion of the periodic table, though, and with modern understanding of chemical bonds as quantum phenomena caused by the pairing of electrons of opposite spins, chemistry as an intellectual discipline looks, to the outsider at least, to have been largely solved.’ But the Babbage from the Economist certainly seems to think so.

Err…I beg to differ and so will the millions of chemist who do research...read more.

Why I should be made the Chief Editor of Chemistry World

The celebration of science occurs annually with the announcement of the Nobel prizes. This is the time when science gets a lot of media coverage and scientists who have made a great impact on human lives are given their due recognition. At about the same time there is also a celebration of geeky humour that happens annually. It’s when the Annals of Improbable Research holds a party at Harvard University where real Nobel prize winners award the Ig Nobel prizes. These prizes are given to discoveries or inventions “that cannot, or should not, be reproduced”...read more

Teach yourself how to multi-task more effectively

An interesting post on MindHacks argued against Maggie Jackson‘s recent book Distracted: The Erosion of Attention and the Coming Dark Age. Maggie claims that with the development of many new technologies that enable us to multi-task, we are getting more stressed and less creative. Vaughan Bell on MindHacks says that the argument is short-sighted and that even before the digital-age we were people who multi-tasked. At least now we have the ability of turning off the devices and thus, turn off the interruptions.

I like some of Vaughan’s argument. He starts by giving example of a woman from a poor neighbourhood who needs to tend to her four children, maintain the house (shopping, cleaning) and take care of a business she runs from the household. The majority of the people in the world who are still not part of the digital age are in one way or the other in that woman’s situation. And thus, saying that multi-tasking is a relatively new thing is not done with.

But he misses to counter some important points from Maggie’s argument. According, to Vaughan it’s easy to see that women may have gotten their brains wired to multi-task but exactly the opposite can then be assumed to be true for men. Men were primarily, hunters and/or gatherers, they had a single objective: feed the family. Thus, they must have got their brains wired to focus on a single task, no?

I’d also like to refute an argument which Maggie makes:

When you’re scattered and diffuse, you’re less creative. When your times of reflection are always punctured, it’s hard to go deeply into problem-solving, into relating, into thinking.

Creativity is the capacity to put together two or more ideas (or things) in a way that no one has before. In that respect, in the digital age I’d say that we have more opportunities to be creative but at the same time, because the same resources are available to a greater audience we have to think much harder and more often about a ‘new way’. That may translate into more time devoted to thinking about the problem but there it doesn’t mean that that time must be all together. I can think of many instances where punctuated thought has brought me more ideas than hours of contemplation.

Today science has come to a point where one needs to be able to think about many things (and use the many resources/tools) at a time to be able to solve the highly complex (and inter-disciplinary) problems. In this case, I’d say that the better we may get at multi-tasking (with or without the help of the new technology) the better it may be for the scientists.

Even then, I have to agree to a few arguments that Maggie makes:

We are programmed to be interrupted. We get an adrenalin jolt when orienting to new stimuli: Our body actually rewards us for paying attention to the new. So in this very fast-paced world, it’s easy and tempting to always react to the new thing. But when we live in a reactive way, we minimize our capacity to pursue goals.

That makes sense. Yes, the multi-tasking on the internet (email, facebook, twitter) might be reducing our capacity to pursue goals. We should realise this in our browsing habits and avoid those distractions. But other than those distractions, that very habit of multi-tasking can prove to be a boon for many researchers, writers, readers or anyone who needs to be able to deal with a lot of data (opinions, facts, ideas) that keeps coming their way during their browsing experience.

Maggie’s comment on Vaughan’s article is a good way of summing things up:

The “concentration oasis” is a myth I don’t subscribe to. And yet it’s truly short-sighted to fail to consider the costs of cultivating a culture of distraction and inattention.

A culture of distraction and inattention can breed from multi-tasking only if our multitasking is left unregulated. I think there is value in multi-tasking but one must teach oneself how to multi-task in a sensible way.

Also posted at the CriticalTwenties blog.

Answer this simple question for me please

I am not the first person asking this question. And you are not the first one to whom I will ask this question. I’ve asked this question even to Nobel laureates (while I was at Lindau) including Sir Harold Kroto and Jean-Marie Lehn but they did not give me a satisfactory answer. I’ve even asked Dr. Evan Harris who said he will email me a reply (which he hasn’t yet).

So here’s the question:

Why is the research funding for science in most countries less than 1% of the GDP?

I can try and make a case for how much scientific research contributes to the GDP but it won’t be as beautiful as Brian Cox’s plea for science funding (which is in fact a TED talk).

In my attempts to try and find an answer to this question, I have come to understand the following:

- An obvious point: Publicly-funded research is mainly towards development of basic science with an aim of publishing in peer-reviewed journals.

- Surprising fact: More application oriented (profit making) research is carried out in the industries (up to 80% in OECD countries but much lesser share in the developing countries).

- Controversial: Some make a case that privately-funded research is more efficient than publicly-funded research. I think that may be the case only in very corrupt countries.

If it is true that such a large chunk of research happens in the industry, it makes me wonder how many secrets are being harbored by the industry and how much good they could do for humanity. But may be that needs to be balanced with the need to keep earning money through licensing patents and selling products to keep innovating.

Leaving the industry aside for the time being, even government funded science amounts to such meager expenses to the state as compared to the impact it has on the economy that today Vince Cable, the Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills, announced that there will be major cuts in science funding. Some guess that the cuts could be as high has 25%.

I fail to understand why. Can someone help me answer this simple question?

Why is the research funding for science in most countries less than 1% of the GDP?

Bonus question: Even if that is the case, why is the government trying to cut that spending?

My old science articles

Before I started writing here at the Field of Science, I had written a few other science articles. I thought it'll be good to share these links with the readers of this blog and this will also serve to archive them for my science blog. So here are the links and brief descriptions of my old science posts:

Polyphasic sleeping: Published at Matters Scientific this article discusses a possible way of reducing the number of hours we sleep by slicing it in to multiple naps.

Synthesising Soufflés: Published in Bang!, Oxford University's science magazine is an article that discusses the science of cooking and the work of Hervé This.

|

| My attempts at Polyphasic Sleeping |

Polyphasic sleeping: Published at Matters Scientific this article discusses a possible way of reducing the number of hours we sleep by slicing it in to multiple naps.

|

| How much is decided before we are born? |

Embroynic Ideas: Published at Matter Scientific this article discusses the impact of stress amongst pregnant mothers on the cognitive abilities of the child.

|

| With Aubrey |

Live long & Proper: Published at LabLit this is an interview of Aubrey de Grey, the author of Ending Aging and the chief scientific officer at SENS.

|

| Brilliant Artwork |

Homeopathic Understanding: Published at Matters Scientific this article describes the attempt of a homeopath in trying to understand how homeopathy works.

|

| Exeter College Chapel |

Green Exeter: Published in Exon, Exeter College's magazine is an article that discusses the debate which led to the college having a meat-free day every week in the college hall.

Science Online London

I will be attending Science Online London or #solo10 on September 3-4 at the British Library. The conference theme is How is the web changing science?

This conference promises to be very different from the Science Communication Conference that happened in May. In the words of an attendee of Science Online 2008 & 2009, "It is a conference which is not just about science communicators."

As a matter of fact, the conference has already begun with many participants attending two simultaneous events that took place tonight one was the tour of diamond light source and the other was a pub crawl in London (hard choice!).

I attended the diamond light source tour for two reasons, one :I do small organic molecule crystallography in my department and some of our crystals do end up going to diamond and two: it is located much closer to Oxford than London. Much of what was talked about at a short presentation before the tour can be found here and then followed a tour of the site. As the synchrotron was off, we could go and look at it from the inside and I really enjoyed the tour.

As for the conference, what I am looking forward to?

- Understanding the future of science journalism

- How to connect the various scientific resources

- The state of science blogging

- How to run a successful social media campaign for science

- How to get scientists to use Web 2.0 tools

- #fringefriv10

And more than that meeting all the wonderful people coming to the conference, especially the mini-Lindau reunion. :)

Deconstructing Homeopathy: An Indian perspective

|

| Courtesy: MSNBC |

In January this year, sceptics from many cities in the UK, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the US staged a stunt where 300 people took large overdoses of homeopathic remedies. Their aim was to demonstrate that homeopathic remedies are nothing but sugar pills and as expected, no volunteer was killed or injured. As 62% of all Indians believe in homeopathy and with that number growing, it is high time that the country begins to understand the science behind homeopathy and the dangers of blindly believing in its claims.

Let’s consider how a homeopathic remedy to treat common cold is made. Homeopaths follow the ‘like cures like’ principle, according to which one must find something that causes the symptoms of common cold like running nose and watery eyes. It is known that onion juice can. So a drop of onion juice is taken and diluted 100 times by adding 100 drops of water. It is then shaken. But that dilution is not enough because homeopaths believe in another principle: ‘the higher the dilution, the higher the potency’, thus one drop of that solution is taken and another 100 drops of water are added to it, followed by more shaking. This is repeated at least 30 times to give the final remedy. At this level of dilution, the chance of finding Barack Obama sitting in your living room is higher than the chance of finding a single molecule of onion juice in that homeopathic remedy. (See BBC documentary to know more)

There have been serious concerns about the validity of homeopathic principles in the mainstream medical community. They lack any scientific evidence and are in complete contrast to the body of knowledge that is traditional medicine. Such highly diluted solutions, which don’t contain even a single molecule of the active ingredient, also make it possible for homeopaths to claim that their remedies have no side effects. Also according to the ‘like cures like’ principle, as stated before, the same homeopathic remedy used to treat stress can simply be used to treat a brain tumour. After all, both conditions cause a headache and the homeopathic remedy for both would simply consist of a highly diluted solution of something that causes a headache.

Many patients who receive homeopathic treatment say that it works for them and it would be wrong to claim that they are lying. Positive effects of homeopathy are merely caused by something called the ‘placebo effect’. A placebo is a medication with no active ingredients in it. The best examples of the placebo effect are observed when two dummy treatments are compared with each other. If one sham treatment works better than the other then it must be simply because people are expecting it to work. For example, a study showed that four sugar pills a day are better at reducing pain than two but more invasive treatment, like a salt-water injection, is even better. In another study patients reported that a red pill was better at treating pain than a white one, even though both were inert.

Homeopathy ‘works’ because of the placebo effect. It doesn’t matter if you are a sceptic, a baby or an animal - if people around you expect the treatment to work, it is more likely to. Sometimes ignorance of important symptoms which need timely attention can give homeopathy credence. This ignorance often makes people wait to see the doctor until their illness is at its worst. At this point a homeopathic remedy is prescribed to the patient. Once the worst is over, the immune system becomes capable of combating the disease and healing begins. But unfortunately, the natural process of healing is often then attributed to homeopathy.

When a homeopathic treatment does not lead to a cure, people tend to blame either their condition or their fate, but still continue to rely blindly on homeopathy. The belief in homeopathy is also perpetuated by India’s unregulated pharmaceutical market which makes it easy to buy medicines across the counter without a physician’s prescription. As a result, people often take the wrong medication and blame the ineffectiveness on mainstream medicine. This tendency generates an undesirable bias towards homeopathy.

One might question that if homoeopathic remedies work (by placebo effect or by self-healing) then surely there is nothing “wrong” in prescribing them? Ethically speaking, it is not wrong to use homeopathic remedies to treat minor illnesses such as common cold or a headache. But it can be exceedingly dangerous, as WHO warned recently, when homeopathy claims to be able to treat serious medical conditions such as cancer, swine flu, AIDS, TB, or malaria.

Furthermore, there can be serious consequences when homeopathy becomes enshrined in mainstream medical policy. In Punjab, for instance a state-wide program is being implemented that uses homeopathic treatment to ‘cure’ pregnant mothers of the need for a C-section during child birth. Incidences like these makes one wonder how many mothers will die and if they do, whether the homeopaths will ever be held to account.

The scientific community has, for decades, systematically refuted every claim that homeopathy makes and yet millions of people in India still believe in it. Government funds it, ministers support it, more colleges are built and more homeopaths walk amongst us year on year. Some say this broad public support for homeopathy remains because the scientific community is unable to communicate this to the people or it comes from a general disdain for “western” medicine.

Also published at the new community blog Critical Twenties.

Further Information:

- BBC Horizon documentary

- Sense about Homeopathy: A Sense about Science publication

- Homeopathic treatment for Ovarian Cysts

- Prasad, R. The Lancet, 2007, 370, 1679

- Samarasekera, U. The Lancet, 2007, 370, 1677

Synthesis of Hygromycin A

|

| Retrosynthetic analysis of Hygromycin by Donohoe et. al. |

Shown to be a broad-spectrum antibiotic which also exhibits immunosuppressant activity, Hygromycin A has an intriguing structure and yet has only been synthesised once before (Ogawa et. al. 24 linear steps and 1% yield). Donohoe's retroysynthesis aims at addressing two key issues in the the sugar moiety: epimerisation at C4 and glycosylation of β-anomer. The route also aims at making use of the group's methodology, the tethered aminohydroxylation (TA) reaction in synthesising the inositol portion.

|

| The TA-reaction at work |

The inositol portion was synthesised using the key TA step which had an superb yield of 74% on using (only) 1 mol% catalyst loading, giving the desired diastereomer exclusively. This step has been improved upon the previously reported result (61% yield at 4 mol% catalyst loading). The attacment of the inositol portion to the B+C part was achieved using standard coupling reagents and on deprotection yielded Hygromycin A in 17 linear steps and 10% overall yield a great improvement over the previous synthesis.

Donohoe, T., Flores, A., Bataille, C., & Churruca, F. (2009). Synthesis of (−)-Hygromycin A: Application of Mitsunobu Glycosylation and Tethered Aminohydroxylation Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 48 (35), 6507-6510 DOI: 10.1002/anie.200902840

We the Molecular Architects

No, I am not talking about Eric Drexler's molecular nanotechnology which is still many many years away, if at all possible. Right now without a second thought I would call organic chemists Molecular Architects, especially the ones who work in the field of Natural Product Synthesis. It is that branch of chemistry that deals with the art and science of constructing complex naturally occurring molecules in the laboratory starting with easily available raw material.

E. Fischer in 1902, H. Fischer in 1930, R. Robinson in 1947, R. B. Woodward in 1965, E. J. Corey in 1990.

I am hoping to write a series of posts on the publications that interest me and I will keep updating this post with the posts in this category.Their contributions are only the few spikes in this field where every molecule synthesised has the potential of making a significant contribution. Every synthesis is a brick (or as Lehn calls it a stone) in this construction of this structure called science, irrespective of it's position in the structure. It helps push the frontiers of the already existing synthetic methods and often leads to new methods helping to build a great library of chemical literature.

Synthesis of Cylindricines

The family of tricylic compounds despite being known to possess no significant biological activity have been a target of many previous syntheses because of it's challenging structure. The paper in discussion today is the synthesis of Cylindricine C synthesised in the Chemistry Research Laboratory at Oxford University which elaborates the use of the recently published methodology by the Donohoe group.

Most of the previously reported synthesis (Snider, Heathcock, Molander, Trost and Kibayashi) have relied upon the late-stage construction of the six-membered B ring but Donohoe's synthesis was planned to begin with the ring B in place. It began with the commercially available picolinic acid which was converted to the disubstituted N-protected pyridine. Then Donohoe and co-workers extended the scope of their own methodology (previously shown N-methyl and N-allyl pyrdinium salts) by showing more examples of Grignard addition to N-DMB protected pyridinium salts.

The key intermediate was prepared in a stereo and regio-selective manner with that methodology. After the ring closure and the subsequent nucleophilic addition of the alkyl Gringard (HexMgBr) gave the desired diastereomer as the major product (X-ray structure). Further maniuplation of the ester side-chain through a series of well-known chemistry yielded them an intermediate aldehyde which could (using Snider's method) lead to cylindricine A, thus completing a formal synthesis of it. Also the same intermediate aldehyde was then converted to give cylidricine C as well.

Donohoe, T., Brian, P., Hargaden, G., & O’Riordan, T. (2010). Synthesis of cylindricine C and a formal synthesis of cylindricine A Tetrahedron, 66 (33), 6411-6420 DOI: 10.1016/j.tet.2010.05.044

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)